One of the most harrowing novels I have ever read is 'Silence', by the celebrated Japanese author, Shusaku Endo. Set in seventeenth century Japan, the novel tells the story of Fr. Sebastiao Rodrigues, a young Portuguese priest hungry for glory and martyrdom, and his personal mission of finding his mentor Fr. Cristovao Ferreira, former provincial of the Jesuits in Japan, who is rumored to have apostasized after several hours of torture. The novel deals with mainly with the question of God's silence, that 'sickening silence', as Fr. Rodrigues puts it, in the face of the many sufferings of the small, withering Christian population in Japan. Why does God permit so much suffering to befall His people?, he asks.Why does God not cry out in defense of His faithful?

The story of the persecution of Christians in Japan is one of bitter pain and sorrowful reticence. Believers were often crucified to bamboo poles made to resemble crosses, as in the case of St. Paul Miki; the bodies were left to hang, and many were encouraged to do violence against them. A common procedure was to skewer the bodies with sharpened bamboo poles, pushed ever so slowly against the bodies of the Christians. In the novel, Endo highlights the use of water torture, in which Christians were tied to stakes and left in the water; the rising tide would do the damage. And perhaps most infamous of all, there was the pit, so-called because Christians were lowered onto a pit filled with all the filth of humanity-- feces, urine, vomit, among others-- to wallow like pigs. The flesh of the head was often cut as well, which served as breeding ground for bacteria. Safe to say, death in the pit-- if death came so quickly from it, that is-- was a very painful way to die.

Fr. Sebastiao Rodrigues has, naturally, been warned of these tortures, and has steeled himself for such a death from the moment he stepped on Japanese soil. But instead of hostile natives, he finds a clandestine community of Christians willing to die for their defense. Thinking himself safe within their community, the young priest starts to emerge from his hiding place more and more, until at last, he is noticed. As a result, the small Christian village becomes the target of greater scrutiny from the feudal lords, and from then on, Fr. Rodrigues begins to realize that martyrdom is not all it is cut out to be. And indeed, the more time he spends in Japan, the more he begins to see that his presence has brought nothing but bad luck to the Christian villages wise, or perhaps foolish, enough to welcome him. There too, is the bumbling, foaming, pathetic shell of man called Kichijiro, who apostasized from Christianity out of cowardice. Seeing his family tortured, but wanting to preserve his life, Kichijiro does the unthinkable and tramples upon the fumie of Christ.

A theme begins to arise at this point: is love worth it? Fr. Rodrigues believes that his mission to this most far flung nation of the earth was motivated by a greater love, a love that desires to unite all men in Christ. But, as he has seen, his love has done nothing but bring sorrow and misfortune to the already withering Christian population of Japan. Is it really love that moves him? And what of Christ, is His own love worth it? The person of Kichijiro represents, for Fr. Rodrigues, man at his most pathetic, that one simply cannot afford to loathe him anymore. Indeed, he adopts a kind of condescending pattering attitude towards Kichijiro. That Christ died for sinners is easy enough to imagine, says Ferreira; but what about the mediocre?

However, it is the seeming indifference of God that troubles Ferreira the most, a God, who, it seems, was content folding His arms while His children suffered on earth. This is bolstered by the various acts of martyrdom that Fr. Rodrigues witnesses, the first, on the coast of the first village, where two young men are submitted to water torture. But there are no choirs of angels to be seen to collect the body of the murdered Christians, no peals of thunder echoing the wrath of God, nothing but the blackness and monotonous ebbing and flowing of an endless sea to accompany the two martyrs to Paradise, if such a concept were even impossible to believe in at tat moment. The second martyrdom sees Fr. Rodrigues captured by the shogun's samurai and brought to prison for questioning, a fate which was orchestrated by Kichijiro himself. Again, the familiar icons of the martyr narrative are gone; there are no hostilities between Rodrigues and his captors at all. On the contrary, he is engaged in theological discussion by a Portuguese-speaking translator and even treated with utmost politeness by Inoue himself, governor of Chikogoku, and sworn enemy of the Christian population in that part of Japan. Indeed, Inoue himself finds nothing wrong with Christian doctrine; he simply believes it will never take root in Japan, and being thus, was useless.

Here, Fr. Rodrigues sees an old, one-eyed man, a Christian like himself, die for Christ, in the most absurdly insignificant way, beheaded suddenly, quickly, nonchalantly, by men with no convictions and no stake and no care for Christianity at all, in short, hired men, with whom he would even occasionally banter. There was no tremor in the earth nor did the skies even darken when the old man died, just the dull and blind groaning of cicadas and the sleepy, noonday heat to witness another man die for the Faith.

However, it is Fr. Rodrigues's meeting with his old mentor, Fr. Ferreira, that most unnerves him. Ferreira had apostasized under torture, and concludes that Christianity would never fully take root in the strange swampy soil of Japan (Ferreira is a historical figure; he later wrote a tract refuting Christianity and became a Zen Buddhist monk). For Fr. Rodrigues, this blow was the most personal, the most damaging. Ferreira had planted the impetus for Rodrigues's desire to evangelize the Indies, but now his own convictions-- the same which planted itself so resolutely in Rodrigues-- was shattered. Eventually Rodrigues himself was to face the pit, and in one of the most haunting scenes in the entire novel, realizes that he, too, must commit the unthinkable, and so steps on the fumie.

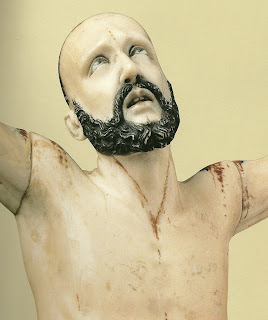

At this point, Fr. Rodrigues realizes that God has never really been silent. As he gazes on the face of Christ, that face which he has clasped to his heart from his childhood, and the same face which, now blackened with the footsteps of thousands of men whose 'feet ached' at what they were about to do, simply stared back at him in agony. From a theological standpoint, we see here the audacious logic of the Incarnation: God emptying Himself of divinity and coming to dwell amongst the misery and grime of creation. Many cultures abound with myths of gods descending from heaven to dwell or mate with humankind, but where Christianity differs is that, Christ alone, of all the gods and demigods, knew the terror of God. There is a line in the novel where Fr. Rodrigues reflects on one of the seven last words of Christ: 'Eloi, Eloi, lama sabacthani', and concludes that, more than a prayer, it too must have 'issued from terror at the silence of God.'

A question is now raised about the nature of love: can God really be called a God of love, even when He has chosen not to eliminate it from the world? Perhaps a deeper issue that lies here is whether or not we think God was right in choosing to suffer with humanity, rather than remove the sufferings altogether. Love is heart-breaking, we often hear it said, but a point we always seem to forget, is that heartbreak hurts, and that it is a kind of hurt which affects both parties. When Fr. Rodrigues tramples on the fumie, he has an epiphany of sorts, and imagines the fumie saying to him:

"Trample! It was to be trampled on by men that I was born into this world. It was to share men's pain that I carried my cross..."

Paradoxically, the greatest act of kindness which Fr. Rodrigues can now do, is to trample on the face of Christ. He is informed by the interpreter that the Christians hanging in the pit have apostasized many times over, but these confessions would be useless until he himself does so. In agony, Rodrigues places his foot on the fumie, and in the spaces between seconds that are eternity, his feet ached, too, and in the far distance, a cock crowed, as it did for St. Peter when he denied Our Lord thrice. Whether Fr. Rodrigues's faith is now completely shattered, like his mentor's, is not explicitly stated, and the novel ends neither confirming nor denying if his moral integrity remained intact. But he is now a haunted man, and cannot now bear to stand to look at Fr. Ferreira, because he only sees the common ugliness that now festers in both of them, the ugliness, and madness, as it were, of love. But that perhaps is what martyrdom, and love, are all about-- to see the ugliness of sin and face it as it is. Fr. Rodrigues's pride demanded a physical, even brutal death in atonement and satisfaction for Ferreira's apostasy, but what was ultimately extracted from him was the crushing of his soul, the meriting of the hatred of the Church and the elect.

In a line from the book, Fr. Rodrigues rationalizes his actions by saying that Christ, too, would have apostasized to save the lives of the Christians; after all, didn't He Himself apostasize, by emptying Himself of divinity? Do not his actions cheat man of God's justice? And most of all, did He not feel the absence of God while He hung on the Cross? If there is a point to be made here, is that to love, to, is to experience terror. Its logic is inscrutable, irrational, even dangerous. But at the same time, can it still be called love if it does not touch on these things? The Japanese Christians could have dumped Christianity en masse and gone back to Shintoism/Buddhism rather than endure suppression and the withering of their numbers. Why, then, did they choose to suffer? Endo gives us a clue by saying that, for the first time in their lives, they were treated as humans, as equals, as faces, by the Portuguese missionaries. In short, it was love that nailed the face of Christ to their breasts, the same way that love held His arms to the wood of the cross. Love, without any hint of polemic, politics, or agenda. There seems to be no other answer.

There, perhaps in a nutshell, is the reason why God has been silent-- because God finally has a face, a beautiful, ugly, sorrowful, agonizing, yet serene face, twisted, beaten, bloody, and yet strangely and profoundly beautiful, all the more so. The ultimate 'folly' of the Incarnation is that the Almighty has come down to be be butchered, to dwell amongst the squalor and misery of human existence. But where are the choirs of angels weeping? Where has their screaming gone? Why hasn't the earth rent itself in twain, and fire consume all creation, in justice for the murder of the Son of God? And we realize, that there is no answer to this question, except the face of Christ, in all its butchered mess, looking back with mournful eyes at humanity, saying, 'I too understand.' All we can hope to do is stare back.

"Eternal Father, turn away Thine angry gaze from all guilty people whose faces have become unsightly in Thy eyes. Look instead upon the face of Thy Beloved Son, for this is the Face of Him in Whom Thou art well pleased. We now offer Thee this Holy face, covered with shame and disfigured by bloody bruises, in reparation for the crimes of our age, in order to appease Thee anger, justly provoked against us. Because Thy Divine Son, our Redeemer, has taken upon His head all the sins of His people that they might be spared, we now beg of Thee, Eternal Father, to grant us mercy. Amen."