"I was afterwards flogged and dressed as a mock king; wounds in the body, 1000. The soldiers who led me to Calvary were 608; those who watched me were 3, and those who mocked me were 1008; the drops of blood which I lost were 28,340."

-Excerpt, "A True Letter of Our Saviour Jesus Christ", Pieta Prayer Booklet

There is something oddly alluring about knowing the exact details of the dolorous Passion of Our Lord. When I first found a copy of the Pieta Prayer Booklet, stashed to the side of folders and other envelopes containing documents in my mother's closet (don't ask), I was instantly captivated by its wealth of promises, revelations, devotions and novenas. The Booklet was old, as evidenced by its crumbling, yellow pages; inside, written in blue ink and in flawless script, was a dedication from my grandparents to my own progenitors. At the margins of some pages, I found blue dots, the occasional underline, and even some liquid stains. It had obviously been used much.

Of course, now that I re-read those same words after a distance of some years, it becomes a lot harder to believe. The skeptic in me loudly wonders how Our Lord could have found the time to count, individually, the number of drops of blood He lost, or how He could, in that bitter hour, have survived such violence and 'live' to tell about it. The whole tone of the letter seems to clinical for me; it reads too much like a counting song, with a definition and certainty that seems so absent in real life, which is full of chaos, despair, and uncertainty. I still appreciated the deep piety and quiet intensity of the prayers, but deep down, I wondered if I could put much so much stock in a mere private revelation. After all, there were the heresiachs and demoniacs currently running the Vatican and who aim for the complete destruction of Tradition to worry about.

In my theology class recently, we started discussing the Resurrection of Christ. As you all know, many Jesuits have crazy ideas, and none are bred wilder and more insane than the controversial theologian Roger Haight, whose book, 'Jesus: Symbol of God' has been damned by the Vatican for its heretical pronouncements on the nature of Our Lord(and rightly so; even my teacher agreed). For Haight, Jesus was the Exemplar-- the homo verus, the genuine man-- Who is at once symbolic of the Father and yet at the same time is distinct from that which He symbolizes. Haight's Christology has been praised by most of the current crop of 'theologians' as a fresh way of examining Christian doctrine in today's post-modern era; he subjects two thousand years of Christian tradition as just another 'phase', a mode of understanding the Divine. In reaching post-modernity, Haight argues that a 'new way' must be devised to see these 'stale' things in a new light.

One of Haight's more 'solid' chapters in the book is the chapter on the Resurrection. In it, Haight argues that the Christ's Resurrection should not be seen as a mere resuscitation, nor as a purely spiritual phenomenon, a position which another liberal theologian, Gerard Loughlin, takes. Haight argues that, since there were no witnesses to the Resurrection event itself, it should not be seen as a purely historical event, but meta-historical. To some degree, I find myself agreeing; in the Philippines, and in many Latin American countries and even Madre Espana herself, a common title for the image of the Risen Lord is Cristo Resucitado, Christ resuscitated. This fails to grasp the full meaning of the Resurrection; it is just another miracle, albeit the greatest one Our Lord performs. If this is the case, then why wasn't Lazarus' resuscitation sufficient to trample down death by death?

The other extreme is the spiritual resurrection. Loughlin argues that the true locus of Christ today is in the action of the Church, His Mystical Body-- but this presence is merely spiritual. To me, this position is simply untenable; I like being made to believe things that are not readily believable. Besides, by this logic, then Elvis Presley is also 'resurrected' in his countless imitators. Consequently, I guess I should revoke my 'membership' in the Church and just hop into the Elvis bandwagon; at least, shiny, rhinestone-buckled shoes look good on them, as do large coiffures. On priests, not so much.

It is so easy to disbelieve these days. We have opportunists at every turn and every corner coming up with 'new research' (which is really nothing than the same old heresies rehashed for a more modern audience) to discredit Christianity. You need only wait for Holy Week and the preceding 'ber' months (that is, September to November) to hear another slew of 'Jesus was only human' hullabaloo from the same, trite, old sources. Of course, globalization also plays its part: nowadays, kids are more concerned with the latest bumble of their teen idols than they are with more important, social concerns. In the Philippines, this is especially true of Westernized rich kids, who have such a warped view of their wealth and such condescension for the concept of noblesse oblige that is not funny anymore. Church just seems to be at the bottom of everyone's priorities.

I would be lying if I said I have never been guilty of what I am writing on before. Truth be told, I simply hate doing chores. The concept of helping others seems more a burden than a duty to me, and I certainly don't like waking up at 6am on a Saturday morning to do that. I could always say, 'I am only human', but I guess that would be like slapping God in the face: in fact, now that I think of it, that answer has been at the forefront of much disbelief among believers. If we hold true to the Christian notion that we are all made in His image and likeness, and if we have such a miserable view of ourselves, the resulting image of God is miserable too. The God Who saves thus slowly morphs to Calvin's greedy, elitist despot, Who is absolutely aloof and is probably an entirely different Being than the God Who appeared to Moses in a burning bush.

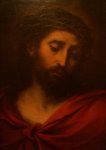

But in the midst of all the suffering, the endless monotony and the dehumanizing rationalization of the world, there, in the middle, stands the Cross of Christ. When I see a crucifix, I cannot help but look at it; most of the time, my reasons are not always pious. I enjoy a finely crafted crucifix, because it pleases my aesthetic; I enjoy looking at one because it just seems so out of this world. In countries where Spanish or Portuguese (add Italian to the list as well) influences were especially dominant, crucifixes take on the most vivid and startling depictions. The corpus is pocked by bruises and oozing with rivers of blood from every wound imaginable; the breast, pierced by a lance, drips with gore, exposing raw muscle and the faintest sliver of bone; the head is brutally adorned by a crown of thorns, cruelly slammed onto His head by a reed. I have said it before and I will say it again: the sight of a crucifix is a powerful sight. It has the power to repulse and edify at the same time.

In Jesus, the events of the Old Testament are summed up and re-enacted with startling economy. In the theology department of the university, there is a painting of Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac, and in the background, snared by a fierce flurry of strokes, was painted the ram 'caught in the thickets'. Who is Jesus here? The answer is both. Indeed, the answer is all: for He, too, was prefigured in the bronze serpent, lifted up high by Moses for all to see, and He too was Job, upon whose frame were heaped the most bitter sorrows.

An interesting episode in the Resurrection narrative was when the apostles did not know they were already speaking to Jesus in the flesh. A face is not something you forget overnight, and a voice is not something that can be drowned in a sea of other voices. So how comes it that His own apostles did not recognize Him? Perhaps they did not really believe His promise at all, or perhaps they were expecting Him to come back to them a bloody mess. I will admit that I do not have a good answer to posit, and if my readers find it so, it has probably been said before by men much wiser than I. For me, the reason why the Apostles failed to recognize Him was because they did not really know Him at all. They confessed Him as the Messiah and vowed to follow Him wherever He would go, but that was about it. Their knowledge of Jesus only became complete when they, too, encountered their own deaths. But their demise should not be seen as something divorced from their persons; their demise was a natural consequence of who they were.

And just who were the Apostles? They were the men that Christ spoke to, but failed to listen; the men that He reprimanded, but continued arguing; the men He died for, but nevertheless remained glued to their despair. The Apostles' encounter with Jesus healed this rift. In the Resurrection, they were no longer just His inner circle, but have themselves been circumscribed by it. It is a strange thing that one could derive such comfort from reading about the tortures and humiliations of a Man who lived more than two thousand years ago, Who died one of the most violent deaths ever demised by His fellow man. St. Josemaria Escriva once wrote in 'The Way' that the Jesus we see in the Cross is not really Jesus; to see Him, we must first deal with ourselves-- by prayer, mortification and sacrifice-- and only then, when the scales from our eyes have fallen, can we truly behold Him in all His glory.

How does one begin to know God, then? The answer lies in the Cross. The answer lies in His Passion and Death. The answer lies in His wounds, the number of drops of blood He lost on the way to Calvary. The answer is in the Church. The answer is in His miracles, the great feasts and days of penitence. To begin to know the Risen Lord, we must first pore over His wounds, the sweltering, pus-infested, wounds from where His blood flowed out and from where the salvation of the world rained down. Then, and only then, when we have encountered Him in His humanity, can we appreciate Him in His fullness.