Some Brief Thoughts

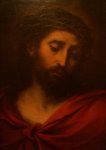

The remarkable thing about the Catholic imagination is, I think, its ability to rehabilitate and reconfigure symbols, ideas, and objects according to its own vision of the world. We see this quite clearly in the most popular expressions of Catholic doctrine; we revere the symbol of a crucified man on a cross, in addition to images of Him being scourged and almost flayed to the bone, as well as images of His infancy (and if you're familiar with Hispanic Catholicism, you may have come across the Santo Nino del Pasion-- the Child Jesus contemplating the very cross on which He is to die). The gruesome character of these images is right to disturb us; the fact that they are revered, blessed, and displayed in our homes might even smack of a bizarre neurosis to some people. Yet Catholicism not only esteems these depictions of its central tenets, but also holds them to be holy.

Perhaps it is a product of purely modern times that we have come to bifurcate the holy from the sacred, not always consciously, but at least in practice. While we may have an understanding of holiness as a kind of moral value par excellence, we fail to see its menace; the holy then, becomes more akin to a celestial ball of fluff than something to be revered, let alone worshipped. At the same time, Catholic doctrine can hardly be said to be 'nice'; Hell remains a metaphysical certainty despite the introduction of pastoral concerns into the present discourse, for example, and no amount of doctrinal wrangling can ever devalue it to the level of mere opinion. Perhaps this is one reason why I am fascinated with Folk Catholicism; it is in its imagination that the colors of the Catholic religious imagination remain most vivid, terrifying, and poetic. The image above is from the Good Friday procession of Procida, a small island to the south of Naples in Italy. It is particularly striking in its depiction of the sacred and the profane in the same tableaux. At the fore of the wagon sits the figure of Death riding a horse, seemingly riding through the desolate waste of a temple. Behind death are the figures of demons, ready to tempt and seduce man into perdition. And behind, the silent, muted, figure of the Dead Christ, ministered to by His angels and surrounded by a golden aureole.

I am honestly confused by the iconography here, but at the same time intrigued. In another float, shown below, we see the Pieta, and on the foreground of the image, a crucified skeleton. I imagine such a juxtaposition of the sacred and the monstrous would send many a finger wagging in disappointment, or else raring to pull the trigger of the flare gun of heresy. I myself am disturbed by it. Then again, I am reminded of the many stories I had heard from my parents and grandparents about Good Friday, and the various superstitions associated therewith. Come twelve noon up to three o'clock, all noise was discouraged under pain of sin. Jumping, smiling, laughing, and speaking were expressly forbidden; God was dead, and all creation ought to weep for His passing. Any sudden or quick movement was seen as an affront to the earth, which housed the body of the Lord; it was reasoned that jumping up and down, for example, caused the earth to press down upon the holy body of the Lord (apparently, He had been swallowed up by the earth), disturbing Him from His rest. These taboos also prescribed on Good Friday a double-faced reputation: on one hand, it is the holiest day in the universe, but at the same time, the most malevolent. Witches, sorcerers, demons and heretics were said to prowl about the world looking to sift the elect as wheat and throw them into everlasting fire. It was also thought to be a most propitious day to cast curses, since, with God dead, there would be no one to punish those who would commit such deeds.

This is probably one reason why the image of the Dead Christ-- the Senor del Santo Sepulcro-- was traditionally thought of as one of the most powerful "avatars" of Our Lord; it represents, simultaneously, the concreteness of man's salvation, the debt to sin having been paid in full by His perfect sacrifice, and at the same time, the powerlessness of man to parlay with the Divine. The destruction of Christ's human body reminds us of our own mortality, but also of the necessity of this destruction, leaving man, effectively, in a double bind: he abhors, and yet needs, perhaps more urgently, the wonderful virtue effected by the sacrifice, and as represented by that particular archetype.

And we have, too, the Anima Sola, the lonely soul of purgatory usually depicted as a beautiful woman, wrists bound by chains, her eyes gazing heavenward, looking for a respite from the burning flame which consumes her body. While we are certainly familiar with the idea of praying for the souls in purgatory, asking their intercession and protection seems alien. Perhaps, to the outside observer looking at this particular facet of Catholic devotion, it might almost look as if one were praying to a soul condemned to burn for all eternity in hellfire. Or worse, a devotee making a plea to some foul succubus to spare himself from damnation. Not just heretical, but also malevolent.

I have remarked before that our present age tends to see God and the celestial Hosts as a collective, cosmic Justice League-- a noble, bland, and thoroughly non-threatening assembly ready to fight our battles for us at the drop of a hat. While I certainly subscribe to the Church's teachings on the matter, one has to wonder if such a desensitized, de-fanged Catholicism would work well enough to save us. The genius of the pre-Vatican II Catholic imagination was how it incorporated all of human existence-- even the tragic and the terrifying-- to paint something coherent. The idea of Hell is admittedly quite terrifying, especially for me, sinner that I am. But, I would rather it be included in the Church's metaphysical horizon than letting me figure out, on my own, what Catholicism is; it is not so much a matter of distrusting my own God-given talents to figure things out, but a matter of realizing how woefully insignificant I am in the grand scheme of things. If we balk at the idea of our own insignificance, it would seem, at least to me, that we have forgotten how to be properly self-centered.

2 comments:

I am blown away, really, by your insights here.

(I have never been able to explain why, on the level of intuition, I have always preferred a Catholic church inundated with the symbolic to the point of tacky excess, over the contemporary, sanitized, cleaned "house". I have long appreciated the power of Catholicism to scare me with its imagery, much how I feel with other faith traditions: the demon looking creatures outside certain Buddhist temples, for example, or the Hindu Kali clutching the skull. These traditions, too, are not devoid of images of peace and light, but, in including the macabre, the blood and the guts of life, one does get the sense that this simply reaches down deeper into the pit of you: it must be more equipped to deal with life as it really is.

Maybe the comforts of contemporary Western society, so alien to suffering (other than, perhaps, the decadent existential variety), have made these images appear irrelevant or even repulsive, for digging up what facts of life we've managed, for the most part, to bury.

It recalls, for me, "Blue Velvet" of David Lynch, where it is the peaceful bright breasted Robin "of love" that plucks the ugly beetle from under the earth.

In that film, what is not mentioned, what is not recorded or expressed in the typical narration, is finally exposed. He takes you through the familiar, then shocks and disgusts you by going further than you are accustomed to going. The dirt and beetles under the tulips of pleasntville suburban life are exposed.

Much of our discourse today, concerning our mortality and fragility, at least, strikes me as hitting that pleasantville tone that Lynch aims to create in portions of his dialogue.

I am commenting particularly on this:

the genius of the pre-Vatican II Catholic imagination was how it incorporated all of human existence-- even the tragic and the terrifying-- to paint something coherent. The idea of Hell is admittedly quite terrifying, especially for me, sinner that I am. But, I would rather it be included in the Church's metaphysical horizon than letting me figure out, on my own, what Catholicism is; it is not so much a matter of distrusting my own God-given talents to figure things out, but a matter of realizing how woefully insignificant I am in the grand scheme of things. If we balk at the idea of our own insignificance, it would seem, at least to me, that we have forgotten how to be properly self-centered.

Hi JD,

Thanks for your comment. It really reminds me of the criticisms hurled against 'Catholic aesthetics' by my Protestant relatives. There is a French term that I cannot really recall right now that translates to 'beautiful-ugly' in English, which I think best describes the 'tacky excess' you refer to. One need only look at the hyper-real images of Our Lord found in Spain, Mexico, the Philippines and Italy to sample this bizarre aesthetic. These images are often life-sized, and typically show Our Lord in His passion. In the Mexican and Philippine traditions, it is common for these statues to be given wigs of real hair or sometimes hemp; they are given embroidered robes with real gold thread and pearls sown into it, as well as rays of gold (in the Spanish tradition, called 'potencias') which protrude from His head. The piety, too, is particularly bone-breaking; it is still a common sight here in Manila, for example, for men and women to approach an image of Our Lord whilst walking on their knees.

I sometimes wonder if such displays of fervid piety, which the Spaniards themselves called 'a most horrible devotion', were already superstitions. But on the other hand, you have, in extremis, the neo-apologetic crowd, which champions an exclusively cerebral understanding of Faith. And one has to wonder: is this self-appointed righteous crowd better for knowing what some Greek and Latin words mean? The paroxysmal devotions of the masses seem an affront to their civil, polite interpretation of Faith. But then, this kind of thinking already presumes Catholicism to be the thinking man's faith, and exclusively such. Never mind the teeming millions in the Third World that bolster the numbers of the Church, sometimes in a manner most revolting (I'm referring here to the squalid living conditions).

My great fear for Catholicism is that it eventually atrophies into a kind of moral suggestion, and ceases to be a vehicle by which man is able to touch the Divine. After all, what would it profit the Church to gain one Newman, at the expense of a million other religiously-illiterate souls?

Post a Comment